Scales and Musical Modes in Celtic, Anglo-American and English Folk Songs

This article should be studied in conjunction with the article Tune Analysis: How To Dissect, Interpret and Categorize Anglo-American, Celtic and English Folk Melodies

Metre

Note that a tune's metre or time signature (3/4, 4/4, 6/8 etc.) does not affect its scale or mode, but is important in determining tune similarities, tune differences, and tune families.

Authentic and Plagal Scales

Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk melodies can be defined as either authentic or plagal. Tunes are divided into these two categories according to where their keynote (almost always their last note) is positioned in relation to the other notes. In an authentic scale the keynote is at the extreme end (usually but not always at the bottom end) of the scale. In contrast, plagal scales have a keynote that is positioned about half way between the lowest and highest notes in the scale. [Roud, Steve and Bishop, Julia (2012) The New Penguin Book of English Folk Songs, pp. lii-liv.] Analysis is complicated, however, because, in Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk song, tunes that present as authentic may have one or more notes that dip below or, more rarely, above the keynote. Such tunes are best categorised as mainly authentic, and such notes are best described as sub-keynotes if they are below the keynote, and super-keynotes if they are above the keynote. A further complication is that the judgment as to whether a tune is mainly authentic or plagal is subjective and can be difficult to call.

Authentic and plagal scales, like metre or time signatures, have no effect on which notes comprise a scale or mode; but, again like time signatures, they are important when analysing tune families and melodic similarities and differences.

Major and Minor Scales

A scale or mode is major if it has a major third, that is to say if the interval between its first and its third notes is two tones (i.e. four semi-tones). Thus, the Ionian, Mixolydian and Lydian scales are major mode scales. A scale or mode is minor if it has a minor third, that is to say if the interval between its first and its third notes is one and a half tones (i.e. three semitones). Thus, the Dorian, Aeolian, Phrygian and Locrian scales are minor mode scales.

Modern Scales and Traditional Modal Scales

There are three scales commonly used in modern popular and art music: the major scale, the harmonic minor scale, and the melodic minor scale. In their ascent all three of these scales have a semitone at the top of their scale as their seventh interval. In their descent the major scale and the harmonic minor scale retain this semitone as their seventh interval; however, the descending melodic minor scale is identical to the descending Aeolian or natural minor scale and has a tone as its seventh interval.

There are four scales commonly used in Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk songs: the major scale (also known as the Ionian scale), the Mixolydian scale, the Dorian scale and the Aeolian (also known as the natural minor) scale. Three of these four scales, namely the Mixolydian, the Dorian and the Aeolian or natural minor scale, have a tone as their seventh interval.

With the development of modern harmony around the early seventeenth century the Mixolydian, Dorian and Aeolian scales fell into decline in popular and, more especially, in sophisticated art music since their whole tone or flattened sevenths were not well suited to harmonisation. As Cecil Sharp and other early collectors noted, however, many of the unaccompanied traditional folk songs that they harvested were in the old modal scales of Mixolydian, Dorian and Aeolian.

Full Scales and Gapped Scales

When analysing a folk melody we need to ascertain the number of notes in the scale. A full scale is heptatonic, or, in plain English, it has seven notes. A gapped scale has fewer than seven notes. If the scale is hexatonic it has six notes. If the scale is pentatonic it has five notes. When determining the number of notes in a scale count two notes that are an octave apart as one note. For example if a tune has notes at 6 different pitches, but two of the notes are an octave apart, for example, one is C (C) and another is upper C (C'), it has a pentatonic scale or mode.

Full Heptatonic Scales

Heptatonic scales can be defined in accordance with the classification system of Glarean, who refers to them as modes.

Heinrich Glarean (in Latin Henricus Glareanus) was born in 1488 and died in 1563. His most famous work, the Dodecachordon, was published in Basle, Switzerland, in 1547 and it established him as a famous and influential musical theorist. [The Dodecachordon (in Latin) and other works by Glarean are available from the International Music Score Library Project at http://imslp.org/wiki/Category:Glareanus,_Henricus] The following is partly based on Glarean’s ideas.

In an octave of music there are twelve notes, separated by semitone intervals. These, marked off by commas, are:

A, A# (or Bb), B, C, C# (or Db), D, D# (or Eb), E, F, F# (or Gb), G, G# (or Ab).

Some avant-garde composers in the twentieth century, notably the Austro-American Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) developed a so-called chromatic scale that included all 12 of these notes. Most composers, however, employ scales of 8 notes, although they may sometimes modulate to a different key without changing the key signature, or add accidental sharps, flats and naturals to give a pleasing or interesting sound or dissonance. In classical music there are three main scales: the major, the melodic minor and the harmonic minor. In Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk melodies the melodic and harmonic minors are not usually used, but the major, as will be seen, is common.

It was Heinrich Glarean who gave to the seven heptatonic scales the names of Ionian, Aeolian, Mixolydian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian and Locrian modes. He believed that this was what they were called in the ancient world. He was quite wrong in this belief, but his nomenclature has nevertheless been retained.

It should be noted that each of Glarean's seven heptatonic scales is diatonic; that is to say that it is a heptatonic or seven note scale with its notes separated by five whole tones (or, in the usage in the USA, whole steps) and two semitones (or, in the US usage, half steps) in each octave. The seven notes C-D-E-F-G-A-B are known as natural notes and they can be played on the white notes of a keyboard. A sequence starting with any one of these seven notes and ending an octave higher on the same note that began the sequence generates a seven note diatonic scale. In all seven of these scales the two semitones are separated from each other by either two whole tones (four semitones) or three whole tones (six semitones). The most important note in a diatonic scale is the keynote or tonic, and the second most important note is the fifth note or dominant. Thus, in the key of C major, C is the most important note and G is the second most important.

The four modes or scales most usually encountered in Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk song are as follows:

1. Ionian/Major Heptatonic Scale

The Ionian mode, which is identical to the Major scale, was, according to Glarean, the one most frequently used by composers in his day. It has also been the most common scale among classical composers. In his analysis in "English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians", Cecil Sharp characterises this scale as Mode 1a+b Heptatonic.

The notes of the C Ionian or C Major scale are C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C’ and you get them by playing upwards from C to C’ on the white notes of a piano, or if, in tonic solfa, you sing the familiar scale of “do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, do”. Note the distribution of tone and semitone intervals in this scale:

C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C’

The above is known as the C Ionian mode because the starting note is C. However, the critical point about any mode is that it always has its semitone intervals in the same place. Indeed, every mode is defined by the position of its semitone intervals. So if, for example, we want to sing the Ionian mode but start on the note of G, we still sing "do re mi..." as before, but start on the G note. However, when we play just up the white keys of a piano we get:

G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G’

...and of course that is wrong, as can be seen by comparison with the previous example, because the second semitone is now in the wrong place. To fix this, we have to use F# (a black key on the piano) instead of F, which gives us the desired result:

G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E-(TONE)-F#-(SEMITONE)-G’

This is called the G Ionian mode, or G Major scale. In fact, we can sing the Ionian mode (or indeed any mode) starting on any note we like. Our starting note is called the key, or tonic. The system of singing "do, re, mi.." is called solfa, thus the system of singing a consistent "do, re, mi..." starting on any tonic is called tonic solfa. It is not the same as the alternative fixed-do system called solfège, which does not concern us here. Tonic solfa is very useful when considering modes, and since the positions of the two semitone intervals are critical to identifying the mode, it is worth noting that they always (and only) occur after the -i words, shown emphasised here: "do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, do".

2. Aeolian/Minor Heptatonic Scale

The Aeolian mode is similar to the modern minor scales in their melodic and harmonic forms but without the accidentals that sharpen, naturalise or flatten some of the notes of those scales. Sharp characterises this scale as Mode 5a+b Heptatonic. The notes of the Aeolian mode in tonic solfa are sung as “la, ti, do, re, mi, fa, so, la”. The A Aeolian notes are A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A’, and you get this scale on a piano when you play upwards from A to A’ on the white keys. Note the distribution of the tone and semitone intervals in this scale:

A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A’

3. Mixolydian Heptatonic Scale

Sharp characterises the Mixolydian mode as Mode 4a+b Heptatonic. The notes of the Mixolydian mode in tonic solfa are sung as “so, la, ti, do, re, mi, fa, so”. The G Mixolydian notes are G, A, B, C, D, E, F, G’, and you get this scale on a piano when you play upwards from G to G’ on the white keys. Again, note the distribution of the tone and semitone intervals in this scale:

G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G’

The Mixolydian mode differs in but one note from the Ionian: the seventh note is flattened to make the final interval of the scale a tone instead of a semitone, and the one before it a semitone instead of a tone.

4. Dorian Heptatonic Scale

Sharp characterises the Dorian mode as Mode 2a+b Heptatonic. The notes of the Dorian mode in tonic solfa are sung as “re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, do, re”. The D Dorian notes are D, E, F, G, A, B, C, D’ and you get this scale on a piano when you play upwards from D to D’ on the white keys. Once more, note the distribution of the tone and semitone intervals in this scale:

D-(TONE)-E-(SEMI-TONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B-(SEMI-TONE)-C-(TONE)-D’

Other Scales

There are three other modal scales. One is the Phrygian mode. Sharp characterises this scale as Mode 5a+b Heptatonic. Its notes in tonic solfa are “mi, fa, so, la, ti, do, re, mi”. The E Phrygian notes are E, F, G, A, B, C, D, E’ and you get this scale on a piano when you play upwards from E to E’ on the white keys. Here is the distribution of the tone and semitone intervals:

E-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E'

Another is the Lydian mode. Sharp characterises this scale as Mode 3a+b Heptatonic. Its notes in tonic solfa are “fa, so, la, ti, do, re, mi, fa”. The F Lydian notes are F, G, A, B, C, D, E, F’ and you get this scale on a piano when you play upwards from F to F’ on the white keys. Here is the distribution of the tone and semitone intervals:

F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F'

Finally there is the Locrian mode. Its notes in tonic solfa are “ti, do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti”. The B Locrian notes are B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B’ and you get this scale on a piano when you play upwards from B to B’ on the white keys. Here is the distribution of the tone and semitone intervals:

B-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B'

The Phrygian mode is rarely encountered in Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk song (though common in Iberian folk music, for example), however, and the full Lydian and Locrian modes scarcely appear at all.

Gapped Hexatonic and Pentatonic Scales

In 1911 the Folk Song Journal published a collection of Celtic folk melodies. Anne G. Gilchrist assigned each tune to its respective scale or mode and wrote a note to explain how and why she had done this.[Gilchrist, Annie G., "Note on the Modal System of Gaelic Tunes," Journal of the Folk-Song Society, Vol. 4, No. 16 (Dec., 1911), pp. 150-153.] Immediately after this note was a gloss from Lucy Broadwood. [Broadwood, Lucy E., "Additional Note on the Gaelic Scale System," Journal of the Folk-Song Society, Vol. 4, No. 16 (Dec., 1911), pp. 154-156.] Both Gilchrist's note and Broadwood's gloss dealt with the question of gapped scales.

Cecil Sharp dedicated two chapters of English Folk Song: Some Conclusions (1907) to a study of the various scales in which English folk songs have come down to us. These are Chapter 5, “The Modes,” and Chapter 6, “English Folk-Scales,” and the topic is also treated elsewhere in that book. Then, in his Introduction to English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians (1917) Sharp includes a section entitled “Scales and Modes.” [Campbell, Olive Dame and Sharp, Cecil J. (1917) English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, pp. xv-xviii.] This begins:

Very nearly all these Appalachian tunes are cast in “gapped” scales, that is to say, scales containing only five, or sometimes six, notes to the octave, instead of the seven with which we are familiar, a “hiatus” or “gap” occurring where a note is omitted.

Sharp then goes on to discuss the prevalence of pentatonic and hexatonic scales in Appalachian music at that time, drawing parallels with Scottish and Irish tunes, and invoking the aid of Gilchrist’s “very clear exposition of this matter” in her note of 1911. He also, most helpfully for later scholars, categorises the musical scale of every tune in the book in accordance with his modified version of Gilchrist’s criteria, as Pentatonic (5 note), Hexatonic (6 note), and Heptatonic (7 note).

It is a useful heuristic and analytical exercise to do as Sharp does. Firstly, to simplify and clarify his analysis he assumes that tunes have been transposed to eliminate the sharps and flats from their key signatures. Secondly, he links gapped scales to their corresponding full scales. If we follow Sharp's method, therefore, we should not consider hexatonic and pentatonic tunes to be in separate hexatonic and pentatonic scales. Instead we should look at them as modal melodies--Ionian/Major, Aeolian, Dorian, Mixolydian, Lydian (a mode included by Sharp despite its rarity as a full scale) and (very occasionally occurring) Phrygian--in which the singers and performers have eschewed one or two of the notes that were theoretically available to them.

This then poses the problematic question as to which notes the singers would have sung if they had used the full seven note scale. Sometimes, as will be seen, this can be deduced, but sometimes it cannot. In some cases we have to make guesses as to what the missing notes would have been. Sometimes we can never definitively know, and this uncertainty, as will be seen, leads to a number of conclusions.

Gapped hexatonic scales in Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk song are all hemitonic or, in other words, they contain a semitone. All gapped pentatonic scales, however, are anhemitonic--i.e. they contain no semitones.

1. Ionian/Major Hexatonic and Pentatonic Scales

1.1 Ionian Hexatonic Scale (Type 1a). This is the Ionian/Major Heptatonic scale with the 3rd (E) note missing. Sharp characterises this scale as 1a Hexatonic.

C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E [missing]-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C’

Thus the notes of the scale are:

C-(TONE)-D-(1.5 TONES)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C’

If a tune transposes to what seems to be C Ionian/C Major but is hexatonic and has no Es there is only one possibility. If the Es were natural, the tune would be C Ionian/C Major. If the Es were flattened the scale would be unviable. The tune must therefore be C Ionian/C Major with a missing 3rd.

1.2 Ionian Hexatonic Scale (Type 1b). This is the Ionian/Major Heptatonic scale with the 7th (B) note missing. Sharp characterises this scale as 1b Hexatonic.

C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B [missing]-(SEMITONE)-C’

Thus the notes of the scale are:

C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(1.5 TONES)-C'

If a tune transposes to what seems to be C Ionian/C Major but is hexatonic and has no Bs in it there are two possibilities. If the Bs were natural, the scale would be C Ionian/C Major. If the Bs were flattened the scale would be C Mixolydian. The tune must therefore be either C Ionian/C Major or C Mixolydian with a missing 7th.

1.3 Ionian Pentatonic Scale. This is the Ionian/Major Heptatonic scale with the 3rd (E) and 7th (B) notes missing. Sharp characterises this scale as 1 Pentatonic.

C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E [missing]-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B [missing]-(SEMITONE)-C’

Thus the notes of the scale are:

C-(TONE)-D-(1.5 TONES)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(1.5 TONES)-C’

If a tune transposes to what seems to be C Ionian/C Major but is pentatonic and has no Bs and also no Es in it there are three possibilities. Firstly, if they had been there, the B and the E might both have been natural to produce a C Ionian/C Major scale. Secondly, the B might have been flattened to produce a C Mixolydian tune. Thirdly, both the B and the E might have been flattened to produce a C Dorian tune.

2. Aeolian/Minor Hexatonic and Pentatonic Scales

2.1 Aeolian Hexatonic Scale (Type 5b).

This is the Aeolian/Minor Heptatonic scale with the 5th (E) note missing. Sharp characterises this scale as 5b Hexatonic.

A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E [missing]-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A'

Thus the notes of the scale are:

A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(1.5 TONES)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A

If a tune transposes to what seems to be A Aeolian/A Minor but has no Es in it there is only one possibility. If the Es were natural the scale would be A Aeolian/A Minor. If the Es were flattened the scale would not be viable. This hexatonic scale can thus be accurately categorised as an A Aeolian/Minor scale with the fifth (E) notes missing.

2.2 Aeolian Hexatonic Scale (Type 5a).

This is the Aeolian/Minor Heptatonic scale with the 2nd (B) note missing. Sharp characterises this scale as 5a Hexatonic.

A-(TONE)-B [missing]-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A

Thus the notes of the scale are:

A-(1.5 TONES)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A

If a tune transposes to what seems to be A Aeolian/A Minor but has no Bs there are two possibilities. If the Bs were natural the scale would have been A Aeolian/A Minor. If the Bs were flattened the scale would have been A Phrygian.

2.3 Aeolian Pentatonic Scale (Type 5).

This is the Aeolian/Minor Heptatonic scale with the 2nd (B) and 5th (E) notes missing. Sharp characterises this scale as 5 Pentatonic.

A-(TONE)-B [missing]-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E [missing]-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A’

Thus the notes of the scale are:

A-(1.5 TONES)-C-(TONE)-D-(1.5 TONES)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A’

If a tune transposes to what seems to be A Aeolian/A Minor but has no Bs and Es in it there are three possibilities. If the Es and the Bs were both natural the scale would be A Aeolian/A Minor. If the Bs were flattened and the Es were natural the scale would be A Phrygian. If both the Bs and the Es were flattened the scale would be A Locrian.

3. Mixolydian Hexatonic and Pentatonic Scales

3.1 Mixolydian Hexatonic Scale (Type 4b).

This is the Mixolydian Heptatonic scale with the 6th (E) notes missing. Sharp characterises this scale as Mode 4b.

G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E [missing]-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G’

Thus the notes of the scale are:

G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(1.5 TONES)-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G’

If a tune transposes to what seems to be G Mixolydian but has no Es in it, there is only one possibility. If the Es were natural the scale would be G Mixolydian. If the Es were flattened the scale would not be viable. This hexatonic scale can thus be accurately categorised as a G Mixolydian scale with the sixth (E) note missing.

3.2 Mixolydian Hexatonic Scale (Type 4a).

This is the Mixolydian Heptatonic scale with the 3rd (B) notes missing. Sharp characterises this scale as Mode 4a.

G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B [missing]-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G’

Thus the notes of the scale are:

G-(TONE)-A-(!.5 TONES)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G’

If a tune transposes to what seems to be G Mixolydian but has no Bs in it there are two possibilities. If the Bs were natural the scale would be G Mixolydian. If the Bs were flattened the scale would be G Dorian.

3.3 Mixolydian Pentatonic Scale (Type 4).

This is the Mixolydian Heptatonic scale with the 3rd (B) and 6th (E) notes missing. Sharp characterises this scale as Mode 4.

G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B [missing]-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E [missing]-(SEMI-TONE)-F-(TONE)-G’

Thus the notes of the scale are:

G-(TONE)-A-(1.5 TONES)-C-(TONE)-D-(1.5 TONES)-F-(TONE)-G’

If a tune transposes to what seems to be G Mixolydian but has no Bs and no Es in it there are three possibilities.. If the Bs and the Es were both natural the scale would be G Mixolydian. If the Bs were flattened and the Es were natural the scale would be G Dorian. If both the Bs ad the Es were flattened the scale would be G Aeolian.

4. Dorian Hexatonic and Pentatonic Scales

4.1 Dorian Hexatonic Scale (Type 2a).

This is the Dorian Heptatonic scale with the 2nd (E) notes missing. Sharp characterises this scale as Mode 2a.

D-(TONE)-E [missing]-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D’

Thus the notes of the scale are:

D-(1.5 TONES)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D’

If a tune transposes to what seems to be D Dorian, but has no Es in it there is only one possibility. If the Es were natural the scale would be D Dorian. If the Es were flattened the scale would not be viable. This hexatonic scale can thus be accurately categorised as a D Dorian scale with the sixth (E) notes missing.

4.2 Dorian Hexatonic Scale (Type 2b).

This is the Dorian Heptatonic scale with the 6th (B) notes missing. Sharp characterises this scale as Mode 2b.

D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B [missing]-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D’

Thus the notes of the scale are:

D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(1.5 TONES)-C-(TONE)-D’

If a tune transposes to what seems to be D Dorian, but has no Bs in it there are two possibilities. If the Bs were natural the scale would be D Dorian. If the Bs were flattened the scale would be D Aeolian.

4.3 Dorian Pentatonic Scale (Type 2).

This is the Dorian Heptatonic scale with the 2nd (E) and 6th (B) notes missing. Sharp characterises this scale as Mode 2.

D-(TONE)-E [missing]-(SEMITONE)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B [missing]-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D’

Thus the notes of the scale are:

D-(1.5 TONES)-F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(1.5 TONES)-C-(TONE)-D’

If a tune transposes to what seems to be D Dorian, but has no Es and no Bs in it there are three possibilities. If the Es and the Bs were both natural the scale would be D Dorian. If the Es were natural and the Bs were flattened the scale would be D Aeolian. If both the Es ad the Bs were flattened the scale would have been D Phrygian.

5. Lydian Hexatonic and Pentatonic Scales

Despite the rarity of Lydian heptatonic scales in Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk melodies, Sharp includes the Lydian heptatonic scale, together with the hexatonic and pentatonic scales that are derived from it, in his listing of tune scales found in Appalachian music, designating them as "Mode 3."

5.1 Lydian Hexatonic Scale (Type 3b).

This is the Lydian Heptatonic scale with the 7th (E) notes missing. Sharp characterises this scale as Mode 3b.

F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E [missing]-(SEMITONE)-F'

Thus the notes of the scale are:

F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(1.5 TONES)-F'

Note that this scale contains a semitone, or, in other words, it is hemitonic.

If a tune transposes to what seems to be F Lydian but has no Es in it there is only one possibility. If the Es were natural the scale would be F Lydian. If the Es were flattened the scale would be unviable. This hexatonic scale can thus be accurately categorised as an F Lydian scale with the 7th (E) notes missing.

5.2 Lydian Hexatonic Scale (Type 3a).

This is the Lydian Heptatonic scale with the 4th (B) notes missing. Sharp characterises this scale as Mode 3a.

F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B [missing]-(SEMITONE)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F'

Thus the notes of the scale are:

F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(1.5 TONES)-C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E-(SEMITONE)-F'

If a tune transposes to what seems to be F Lydian but has no Bs in it there are two possibilities. If the Bs were natural the scale would be F Lydian. If the Bs were flattened the scale would be F Ionian/F Major.

5.3 Lydian Pentatonic Scale (Type 3).

This is the Lydian Heptatonic scale with the 4th (B) and the 7th (E) notes missing. Sharp characterises this scale as Mode 3.

F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(TONE)-B [missing]-(SEMITONE) C-(TONE)-D-(TONE)-E [missing]-(SEMITONE)-F'

Thus the notes of the scale are:

F-(TONE)-G-(TONE)-A-(1.5 TONES)-C-(TONE)-D-(1.5 TONES)-F'

If a tune transposes to what seems to be F Lydian, but has no Bs and no Es in it there are three possibilities. If the Bs and the Es were both natural the scale would be F Lydian. If the Bs were flattened and the Es were natural the scale would be F Ionian/F Major. If both the Bs and the Es were flattened the scale would be F Mixolydian.

6. Phrygian and Locrian Gapped Scales

Sharp makes little or no mention of these, presumably since he did not encounter them in the Appalachians, but also perhaps because they do not fit neatly into his system. Certainly Phrygian and Locrian heptatonic scales are very rare in Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk melody. However, for the sake of completeness, and since the classification of pentatonic tunes in particular is problematic, clarification is needed. Essentially, the difficulty is caused by the elimination of semitone intervals. We can see this most clearly by looking again at the gapped scales, but this time in tonic solfa. Sharp's system essentially takes out mi or ti for the hexatonic forms, and mi and ti for the pentatonic forms, as shown below:

Ionian full: do re mi fa so la ti do

Ionian hexatonic: do re -- fa so la ti do or do re mi fa so la -- do

Ionian pentatonic: do re -- fa so la -- do

Aeolian full: la ti do re mi fa so la

Aeolian hexatonic: la -- do re mi fa so la or la ti do re -- fa so la

Aeolian pentatonic: la -- do re -- fa so la

Mixolydian full: so la ti do re mi fa so

Mixolydian hexatonic: so la -- do re mi fa so or so la ti do re -- fa so

Mixolydian pentatonic: so la -- do re -- fa so

Dorian full: re mi fa so la ti do re

Dorian hexatonic: re -- fa so la ti do re or re mi fa so la -- do re

Dorian pentatonic: re -- fa so la -- do re

Lydian full: fa so la ti do re mi fa

Lydian hexatonic: fa so la -- do re mi fa or fa so la ti do re -- fa

Lydian pentatonic: fa so la -- do re -- fa

That is all well and good, but what happens when the mode starts with mi, as it does with Phrygian, or ti, as it does with Locrian? Clearly, we cannot take out the tonic notes! Instead, to get rid of the semitone intervals we have to remove fa in the case of Phrygian and do in the case of Locrian. That means that we potentially now have two pentatonic forms for each of these modes, whereas there is only one such form for the other modes. Here are the gapped scales for these two modes.

Phrygian full: mi fa so la ti do re mi

Phrygian hexatonic: mi -- so la ti do re mi or mi fa so la -- do re mi

Phrygian pentatonic: mi -- so la -- do re mi [or mi -- so la ti -- re mi]

In practice, the second form of the pentatonic Phrygian would not be used because it lacks do, the note that underpins the entire tonal system, thus there is really only one form.

Locrian full: ti do re mi fa so la ti

Locrian hexatonic: ti -- re mi fa so la ti or ti do re -- fa so la ti

Locrian pentatonic: [ti -- re -- fa so la ti or] ti -- re mi -- so la ti

With Locrian, however, there is no choice; do has to go, which is the reason why Locrian sounds so strange to our ears, because we have lost that underpinning note, thus the scale seems unstable. In the first pentatonic form, though, the gaps are really too close for comfort, being separated by only one note (re), so in practice the second pentatonic form would be used.

As pointed out earlier, when considering the other modes, there are alternative interpretations of the pentatonic forms if we insert sharpened or flattened notes in the gaps. For completeness, we need to consider both pentatonic forms in each of the Phrygian and Locrian too.

In the Phrygian first form, if we restore the fa and sharpen it (fi) and restore the ti, we get a transposed form of the Aeolian: mi fi so la ti do re mi, which we can see from the positions of the semitone intervals marked by the notes in bold. (Please refer to the full list above, and remember that it is the relative positions of the semitones that determine the mode). The same thing happens in the second form if we restore the fa and sharpen it (fi) and restore the do.

Alternatively, if in the first form we restore the fa without sharpening it and restore the ti and flatten it (ta), we get a transposed version of the Locrian: mi fa so la ta do re mi.

Additionally, for the Phrygian second form, if we restore the fa and sharpen it (fi) and restore the do and sharpen it (di), we get a transposed form of the Dorian: mi fi so la ti di re mi, again revealed by the semitone positions.

In the Locrian second pentatonic form, if we restore the do and then restore the fa and sharpen it (fi), we get a transposed form of the Phrygian: ti do re mi fi so la ti.

Alternatively, if we restore the do and sharpen it (di) and restore the fa and sharpen it (fi), we get a transposed version of the Aeolian: ti di re mi fi so la ti.

The above ambiguities mean that it can be extremely difficult if not impossible to establish exactly what the mode of a gapped scale is.

Scales, Modes and Key Signatures

There are 15 possible key signatures and, in theory, 21 possible keynotes (A, A#, Ab; B, B#, Bb; C, C#, Cb; D, D#, Db; E, E#, Eb; F, F#, Fb; G, G#, Gb). Of the 15 x 21 =315 scales that it is possible to generate, however, 43 are either unviable or duplicates. For example, any D# key (Major, Minor or whatever) contains exactly the same note pitches as its equivalent Eb key. Here is a table of the theoretical possibilities, with the unviable and duplicate scales indicated in red text:

File:Tune Analysis Table 1 of 4-Full Unredacted Table of Scales and Modes.pdf

And here is another table with the unviable and duplicate scales edited out:

File:Tune Analysis Table 2 of 4-Table of Scales and Modes First Redaction.pdf

In addition, it is very rare for Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk songs to be notated in remote keys with more than 4 sharps or flats in them; here is a table with the remote keys edited out:

File:Tune Analysis Table 3 of 4-Table of Scales and Modes Second Redaction.pdf

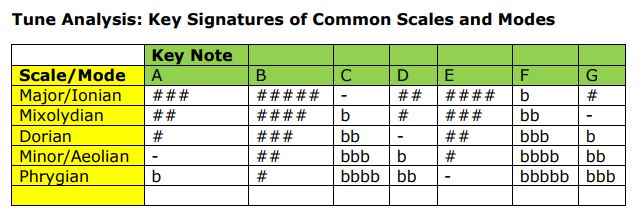

With regard to Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk songs the question can be further simplified. There are practically no Locrian or Lydian scales and the Phrygian scale is rare. Furthermore most Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk songs are notated into keys with no sharps or flats in the key signature (i.e. keys such as C# minor, Bb Major, etc. are usually avoided). Here is a simplified table that is applicable to nearly all Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk songs:

A PDF version of the above table is available here.File:Tune Analysis Table 4 of 4-Key Signatures of Common Scales and Modes.pdf

Remember, however, that, as explained, it might not be possible to allocate a single definitive mode to gapped scales.

Note that the scale or mode of a melody does not affect its pitch. This is determined by the key. For example, the keys of C Major and F Major have the same scale or mode, but F Major is 2.5 tones higher in pitch than C Major. It follows that the key signature is not relevant to the analysis of tune similarities and differences. To facilitate such analysis (for example, when investigating possible tune families of similar melodies) computer software can be used to alter the pitch of the melodies by removing the sharps and flats from their key signatures.

Summary and Conclusions

It is useful heuristically and analytically to follow the practice of Cecil Sharp and link gapped (hexatonic and pentatonic) scales to the full (heptatonic) scales with which they are associated.

If gapped scales in Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk melodies are transposed to remove the sharps and flats from their key signatures the following is true.

1. All hexatonic scales contain a semitone and are thus hemitonic.

2. No pentatonic scales contain a semitone and are thus all anhemitonic.

3. The hexatonic scales that can be linked to the Ionian/Major, Aeolian/Minor, Mixolydian, Dorian and Lydian heptatonic scales lack either their B notes or their E notes and the pentatonic scales lack both their B notes and their E notes.

4. Hexatonic scales that can be linked to the Ionian/Major, Aeolian/Minor, Mixolydian, Dorian and Lydian heptatonic scales and that lack their E notes can be characterised as being in one possible mode; this is the same mode as the heptatonic scale created if an E natural is added to the existing six notes.

5. Hexatonic scales that can be linked to the Ionian/Major, Aeolian/Minor, Mixolydian, Dorian and Lydian heptatonic scales and that lack their B notes can be characterised as being in two possible modes. This is either the same mode as the heptatonic scale created if a B natural is added to the existing six notes; or it is the same mode as the heptatonic scale created if a B flat is added to the existing six notes.

6. Pentatonic scales that can be linked to the Ionian/Major, Aeolian/Minor, Mixolydian, Dorian and Lydian heptatonic scales and that lack both their B notes and their E notes can be characterised as being in three possible modes. This is either the same mode as the heptatonic scale created if a B natural and an E natural are added to the existing five notes; or it is the same mode as the heptatonic scale created if a B flat and an E natural are added to the existing five notes; or it is the same mode as the heptatonic scale created if both a B flat and an E flat are added to the existing 5 notes.

7. Given the rarity of the Phrygian heptatonic scale in Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk melody it is probably appropriate to classify gapped scales that could theoretically be linked to the Phrygian heptatonic scale as linked instead to the Aeolian/Minor or Dorian heptatonic scales.

8, Given the rarity of the Locrian heptatonic scales in Celtic, Anglo-American and English folk melody it is probably appropriate to classify gapped scales that could theoretically be linked to the Locrian heptatonic scale as linked instead to the Aeolian/Minor heptatonic scale.

Thus gapped scales can be linked to all of the full heptatonic scales identified by Glarean, namely Ionian/Major, Aeolian/Minor, Mixolydian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian and Locrian. Moreover, every pentatonic scale can be theoretically linked to 3 different heptatonic scales.

Addendum: Percy Grainger and the Modes

In 1908 Percy Grainger wrote:

My conception of folk-scales, after a study of them in the phonograph, may be summed up as follows: that the singers from whom I recorded do not seem to me to have sung in three different and distinct modes (Mixolydian, Dorian, Aeolean), but to have rendered their modal songs in one single loosely-knit modal folk-song scale, embracing within itself the combined Mixolydian, Dorian and Aeolean characteristics. [Percy Grainger, ‘Collecting with the Phonograph’, Journal of the Folk Song Society, 3 (1908), 147-242 (p. 158).]

Beneath this there came a reply:

The Editing Committee …wish to point out that the general experience of collectors goes to show that English singers most rarely alter their mode in singing the same song. [Ibid., p. 159.]

On both sides the debate was courteous and respectful, with Grainger adding that his suggestion was “put forward in all tentativeness,” and his editors praising his “most careful observations.” But the question is raised: who was correct?

In 2013 Lewis Jones analysed a random sample of 103 tunes from the Butterworth MSS. [Jones, Lewis (2015) "Modal Scales in English Folk Song: An Analysis with Reference to the George Butterworth Collection," Proceedings of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, Folk Song Conference 2013, pp. 157-165.] Of these 86 were purely modal (Major/Ionian, Dorian, Mixolydian or Aeolian). Of the remaining 16 tunes 13 modulated between Major/Ionian and Mixolydian. This, argued Jones, was explicable by the similarity of the two scales--they are identical except for one note (the seventh) of each scale. Of the remaining 3 tunes 2 were Aeolian with Dorian influence and 1 (for a single note) was Dorian with Mixolydian influence.

Thus, on the basis of this sample, Grainger would appear to be wrong and the editors of the Folk Song Journal correct. Jones found little evidence of Grainger's "one single loosely-knit modal folk-song scale, embracing within itself the combined Mixolydian, Dorian and Aeolian characteristics."

The Mixolydian, Dorian and Aeolian scales share 5 common notes, namely the first (keynote), the second, the fourth, the fifth and the seventh. The notes that vary in pitch in these three modes are the third and the sixth.

One way to investigate Grainger's claim is to transpose modal heptatonic tunes to remove the sharps and flats from their key signatures. This exercise has three possible outcomes.

1. Mixolydian tunes will display G as their keynote. We can then see whether any of the thirds (the Bs) are flattened. If they are the tune modulates between Mixolydian and Dorian. If, in addition, any of the sixths (the Es) are flattened, the tune modulates between Mixolydian, Dorian and Aeolian.

2. Dorian tunes will display D as their keynote. We can then see whether any of the thirds (the Fs) are sharpened. If they are the tune modulates between Dorian and Mixolydian. If, in addition, any of the sixths (the Bs) are flattened, the tune modulates between Dorian, Mixolydian and Aeolian.

3. Aeolian tunes will display A as their keynote. We can then see whether any of the sixths (Fs) are sharpened. If they are the tune modulates between Aeolian and Dorian. If, in addition, any of the thirds (Cs) are sharpened, the tune modulates between Aeolian, Dorian, and Mixolydian.

To systematically test whether Grainger is correct we would need to investigate whether or not such tunes exist, not only in MSS collections but also in audio records that are as yet unconverted to musical notation.

Present evidence suggests that both Grainger's editors and Grainger were wrong. Some tunes modulate between Ionian and Mixolydian (Ionian/Mixolydian hybrids), between Mixolydian and Dorian (Mixolydian/Dorian hybrids) and between Dorian and Aeolian (Dorian/Aeolian hybrids) because those linked scales only differ from each other by one note. But very few tunes modulate between all three of the modes Mixolydian, Dorian and Aeolian. This undermines both the Editing Committee's assertion that "English singers most rarely alter their mode in singing the same song" and Grainger's claim that there was "one single loosely-knit modal folk-song scale, embracing within itself the combined Mixolydian, Dorian and Aeolian characteristics."